* Warning: The following content contains disturbing and violent images that may be triggering.

Six thousand, five hundred.

That’s the approximate number of Black people lynched in the U.S. between 1865 and 1950—at least, those that are known—according to the Equal Justice Initiative.

Lynching (definition): a murder outside of the judicial process—including but not limited to hangings, typically done by a mob.

People of African descent have endured racial oppression and brutality on American soil from the moment the first slave ship arrived with human cargo in 1619. But even though slavery was legally abolished in 1865, the horrors of the shackle and the whip were followed by new kinds of terrorism and violence toward Black people that have persisted throughout the nation’s history. Sometimes, it's been committed by hate groups like the Ku Klux Klan. Sometimes, it's been the act of a single individual. And sometimes, it's even been treated as an open public spectacle. In all cases, racially motivated violence has remained a powerful tool to reinforce white supremacy, dehumanize Black people and intimidate them from seeking progress, equality—or even stability.

The details of most lynchings and other acts of racial violence remain lost to history. But the bloodshed described below captured broader attention, inspiring outrage, activism—and in some cases, a measure of progress.

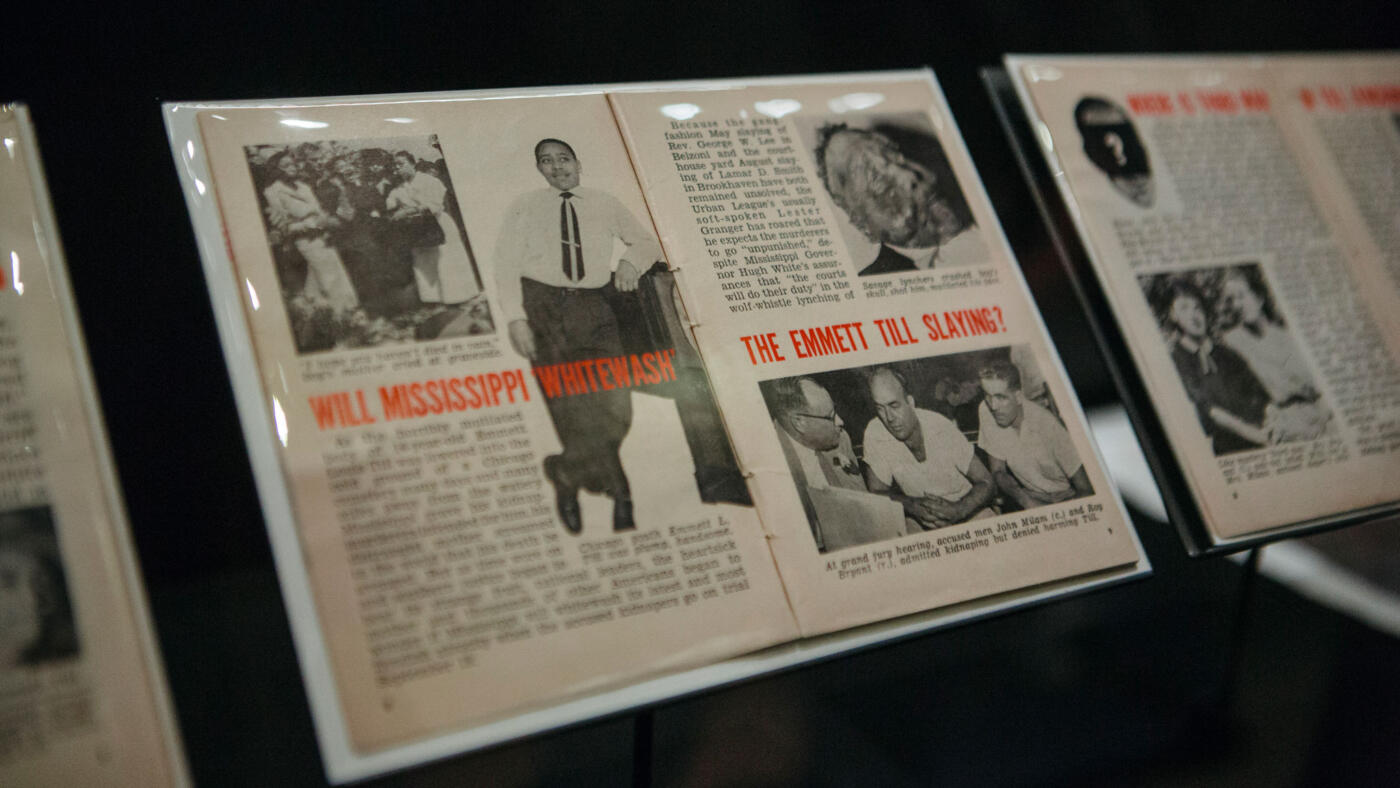

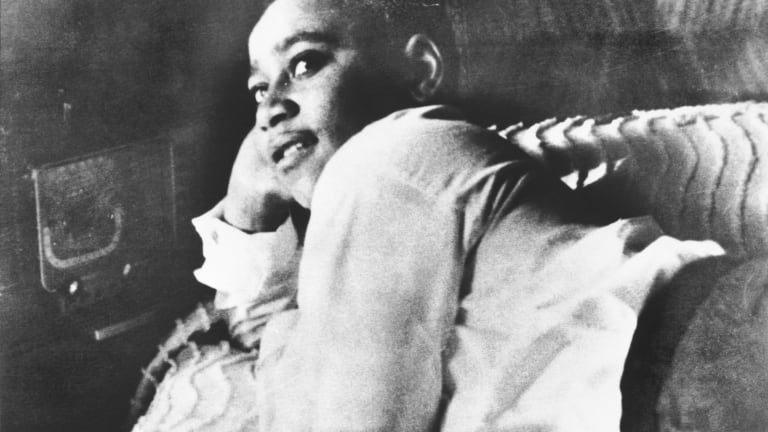

Emmett Till

August 28, 1955 / Money, Mississippi

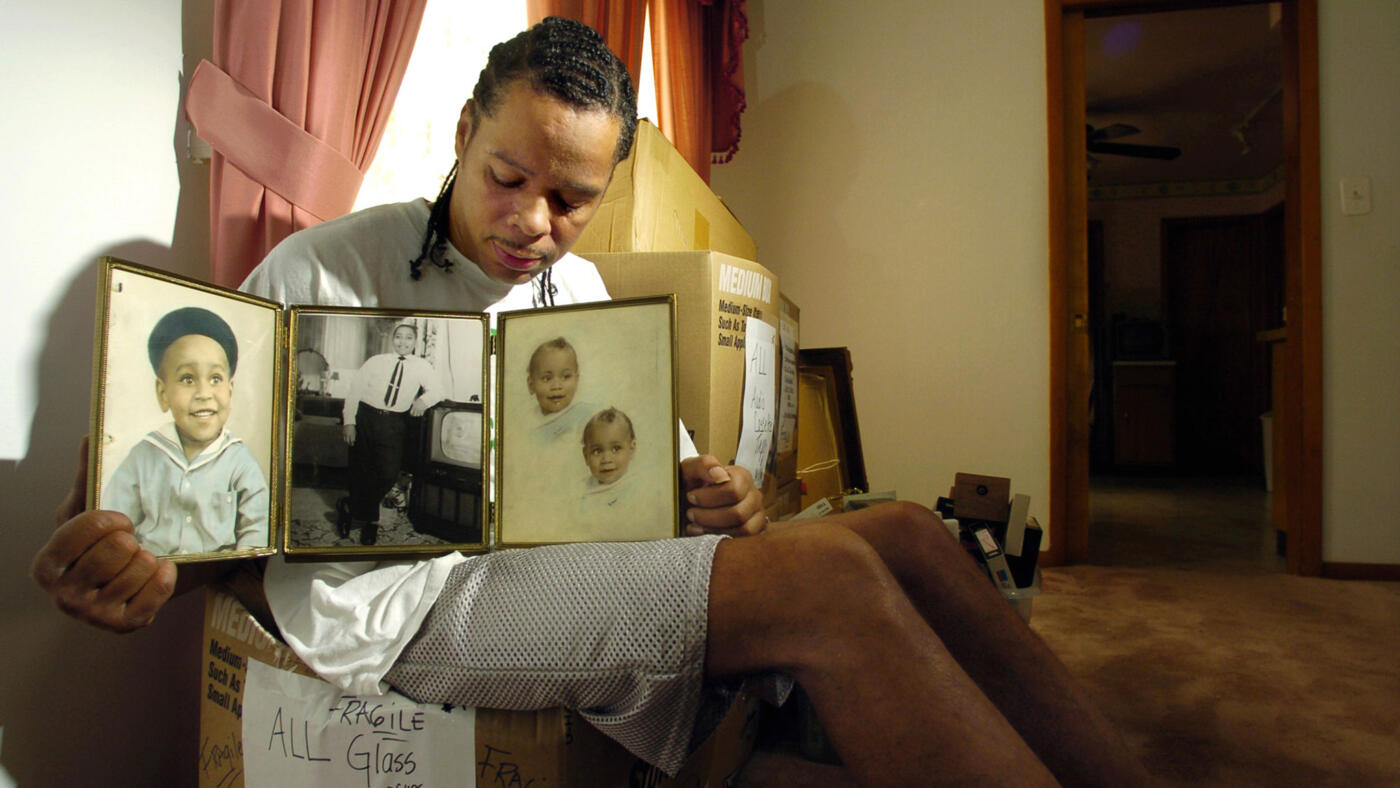

When 14 year-old Emmett Till was murdered in 1955, his shockingly brutal death became a catalyst for the civil rights movement. Born and raised in Chicago, Till was no different from an average teen: According to his cousin Wheeler Parker, he was a prankster, had a soft spot for animals and loved being the center of attention. He also loved his family, taking up many household duties to support his mother Mamie Till-Mobley.

“Emmett had all the house responsibility,” she later recalled. “He cleaned…cooked quite a bit…even took over the laundry.”

In August 1955, Emmett joined his uncle Moses Wright and 16-year-old cousin Wheeler on

a trip to visit family, in Money, Mississippi—his first experience of the rural South. He and Wheeler helped family pick their cotton crops, then cooled off with a swim. Their first few days in Money were filled with family, laughter and

fun.

Then, on August 24, Till, Parker and a few other teens went to Bryant’s Grocery and Meat Market for some

refreshment. Accounts of the incident differ, but Parker—a direct eyewitness—says Emmett

whistled at Carolyn Bryant, the store owner’s wife.

‘Even now, we don’t know what possessed him. He…didn’t have any idea [of] the danger.’

// Emmett Till’s cousin Wheeler Parker, oral history interview with the Library of Congress

Late on the night of August 28, Carolyn’s husband Roy Bryant and his half-brother J.W. Milam arrived at Wright’s home, declaring they “were looking for the boy that did the talking” and dragging Till off in their car. Three days later, the

teen’s mutilated body was found in the Tallahatchie River—savagely beaten, shot in the head, his neck tied to a massive fan with barbed wire. The bright-eyed, upbeat boy was unrecognizable.

Gutted by grief, Till’s mother nonetheless stood strong, determined to show the world the atrocity committed against her child. “That body was half-buried literally in Mississippi, and if it would've been all the way buried, we wouldn't

know who Emmett Till was,” says Dave Tell, author of Remembering Emmett Till. “She got on the phone, she

convinced them to send the body back North.”

She didn’t stop there. Mamie decided on an open casket at Emmett’s public funeral, exposing her son’s disfigured face to the nearly 50,000 mourners—and permitting wide distribution of photographs, including a national Jet magazine

spread. Circulated just as the civil rights movement was beginning to mobilize, the graphic images literally put a

face to the growing outcry against racial violence in America. Bryant and Milam’s quick acquittal by an all-white jury only fueled the national outrage. Bryant’s wife, Carolyn, recanted her accusation decades later.

Emmett’s story might have passed virtually unnoticed had Mamie not continued to push it out into the world, even embarking on a speaking tour for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Her son’s death not only inspired local activists to fight for justice, but sparked embers of resistance in the broader

civil rights struggle. One hundred days after Till’s death, Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a bus, resulting in the Montgomery Bus Boycott—and a later Supreme Court desegregation decision.

“Rosa said she thought about going to the back of the bus,” civil rights leader Rev. Jesse Jackson told Vanity Fair in 1988. “But then she thought about Emmett Till and she couldn’t do it.”

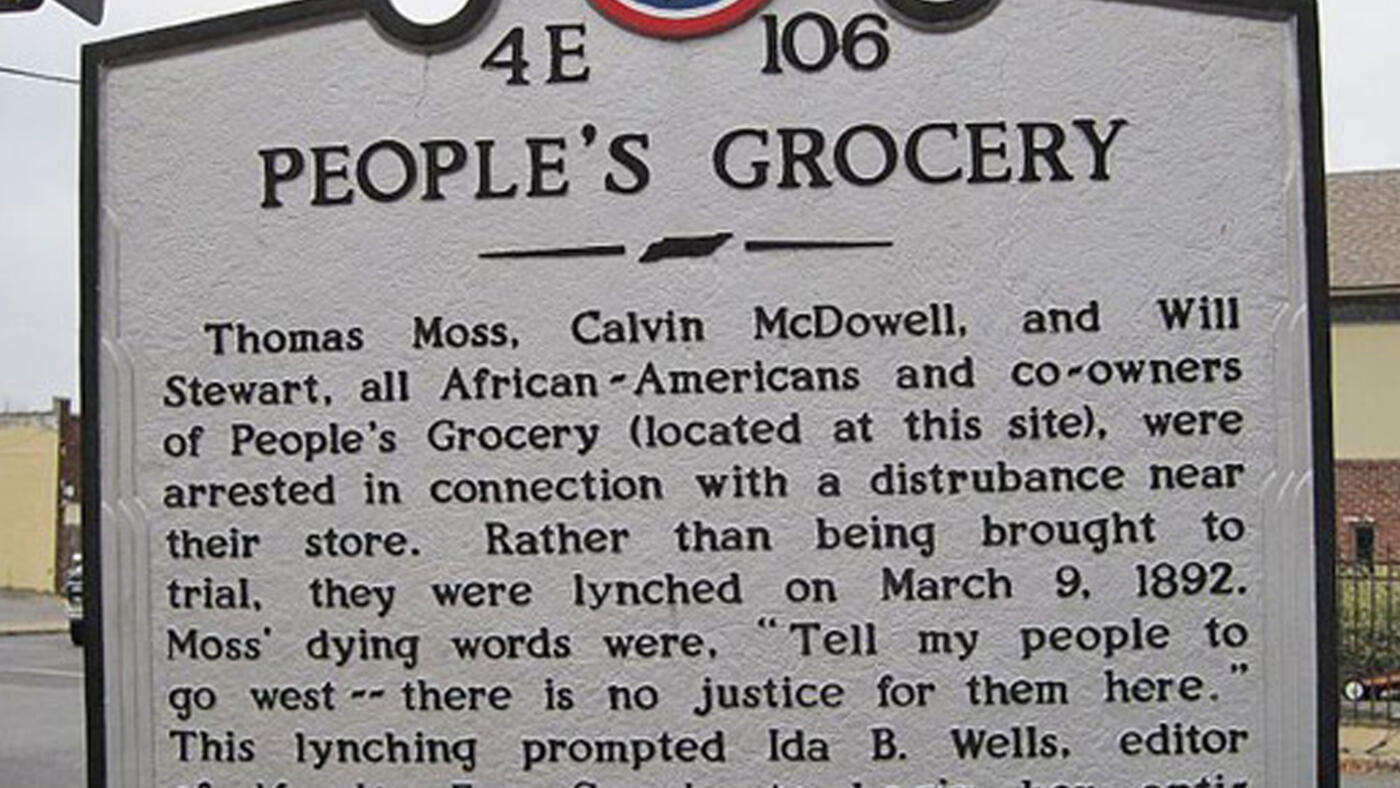

Thomas Moss, Will Stewart and Calvin McDowell

March 9, 1892 / Memphis, Tennessee

In the decades after the Emancipation Proclamation, African Americans worked to build their lives

and livelihoods from less than nothing. Despite steep challenges, Black businesses began to blossom in the late 19th century. In the “Curve” neighborhood of Memphis, co-owners of the thriving People’s Grocery, Will Stewart, Calvin McDowell

and Thomas Moss, brought pride—and much-needed capital—to their mixed-race neighborhood.

Moss, in particular, earned praise for his community involvement, as a mail carrier as well as a successful business owner. “A finer, cleaner man than he never walked the streets of Memphis,” wrote his close friend, fellow Memphis resident and emerging journalist Ida B.

Wells, in her autobiography Crusade for Justice. “He was well liked, a favorite with everybody; yet he was murdered with no more consideration than if he had been a dog.”

The growth of the People’s Grocery had come at the expense of local white competitor William Barrett, who began fanning racial tensions. Following several neighborhood incidents, he alleged to a local judge that Black locals, including his

business rivals, were conspiring against the Curve’s white residents.

That night, the county sheriff and a group of deputized citizens surrounded the Black grocery in an armed standoff. After white men were injured in the exchange, Stewart, McDowell and Moss were all arrested, along with dozens of alleged

Black co-conspirators. Early in the morning of March 9, a local mob took justice into their own hands, storming the jail, dragging the men from their cells and, as the Memphis Appeal-Avalanche reported, brutally murdering them with “more shots

than were necessary to cause death.”

‘Tell my people to go West. There is no justice for them here.’

// Thomas Moss’s reported last words

This became a watershed moment for Wells. Deeply affected by the gruesome murder of her friend, she shifted her journalistic focus to the growing epidemic of racially inspired killings. In an editorial published two months later—the first in what would become her famed anti-lynching series—Wells

specifically called out the murder of the three grocers, while debunking the trope of Black men raping white women, a common pretext used to justify lynchings.

Instead, she asserted, these atrocities were far more often about squashing Black economic

progress: “an excuse to get rid of Negroes who were acquiring wealth and property and thus keep the race terrorized and ‘keep the n----r’ down.’” Her editorial prompted a violent attack on Wells’ newspaper office—and threats on her

life. Heeding her friend’s warning, she encouraged Black Memphis residents to leave the city, which she said didn’t value their lives. More than 6,000 fled, and she herself became an exile, moved to a lifetime of activism.

Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith

August 7, 1930 / Marion, Indiana

As Wells observed, white communities frequently justified lynchings by claiming to protect and avenge their women. The myth of “savage” Black men raping white women, popularized in the 1915 film Birth of a Nation, continued well into the 20th century, epitomized by cases such as that of the falsely accused Scottsboro Boys. However, it was the 1930 rape allegations against Thomas Shipp, Abram Smith and James Cameron that

resulted in one of the nation’s most gruesome images of mob lynching—which, in turn, inspired an iconic anti-lynching anthem,

indelibly memorialized by jazz singer Billie Holiday.

The three Black teenagers had been friends in the small town of Marion, Indiana. On the night of August 6, after an afternoon playing horseshoes, Shipp, 19, and Smith, 18, told 16-year-old Cameron they’d decided to “stick up” an

unsuspecting white couple at a local lover’s lane. But the robbery went wrong. According to Cameron’s memoir A Time of Terror: A Survivor's

Story, he recognized the man, Claude Deeter, as a customer of his shoeshine stand and fled the scene, hearing shots as he ran. With Deeter dead and his companion Mary Ball claiming she was raped by all three teenagers, the

teens were arrested—but there would be no trial.

Wielding sledge hammers, bats and crowbars, vigilantes overtook the jail and, one by one, dragged the young men outside, where an

estimated 10,000 to 15,000 people had rallied. As Cameron watched from his cell, Smith was beaten to

death before his body was strung from a tree. Shipp attempted to free himself from his noose, but had his arms broken before being hoisted back into the air. When it was his turn, Cameron—with the noose already around his neck—was

improbably saved by a voice in the crowd proclaiming his innocence. He returned to jail and was ultimately convicted, serving four years. Mary Ball later recanted her rape accusation.

Local photographer Lawrence Beitler captured the brutal scene: Shipp and Smith’s bloodied, disfigured bodies hanging above a densely packed crowd—some smiling, one posing and pointing. Demand for the image ran high, and Beitler printed thousands of copies, selling the macabre mementos for 50 cents each.

After circulating for years, the graphic “postcard” reached Bronx high school educator Abel Meerpol, who was moved to write the 1937 poem that would eventually become “Strange Fruit.”

‘Southern trees bear a strange fruit

Blood on the leaves and blood at the root

Black body swinging in the Southern breeze

Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees.’

// A verse from ‘Strange Fruit’

Billie Holiday recorded the song as a tribute to her father who died of a lung disorder, denied proper medical care because

of his race. Her insistence on singing the tune at nightclubs left patrons uncomfortable and stunned—and helped tank her

career. Still, it became an enduring anti-lynching anthem. As for Cameron, he was forever changed after the trauma of his attempted lynching, becoming a passionate civil rights advocate and going on to found the American Black Holocaust Museum. He was officially pardoned in 1993.

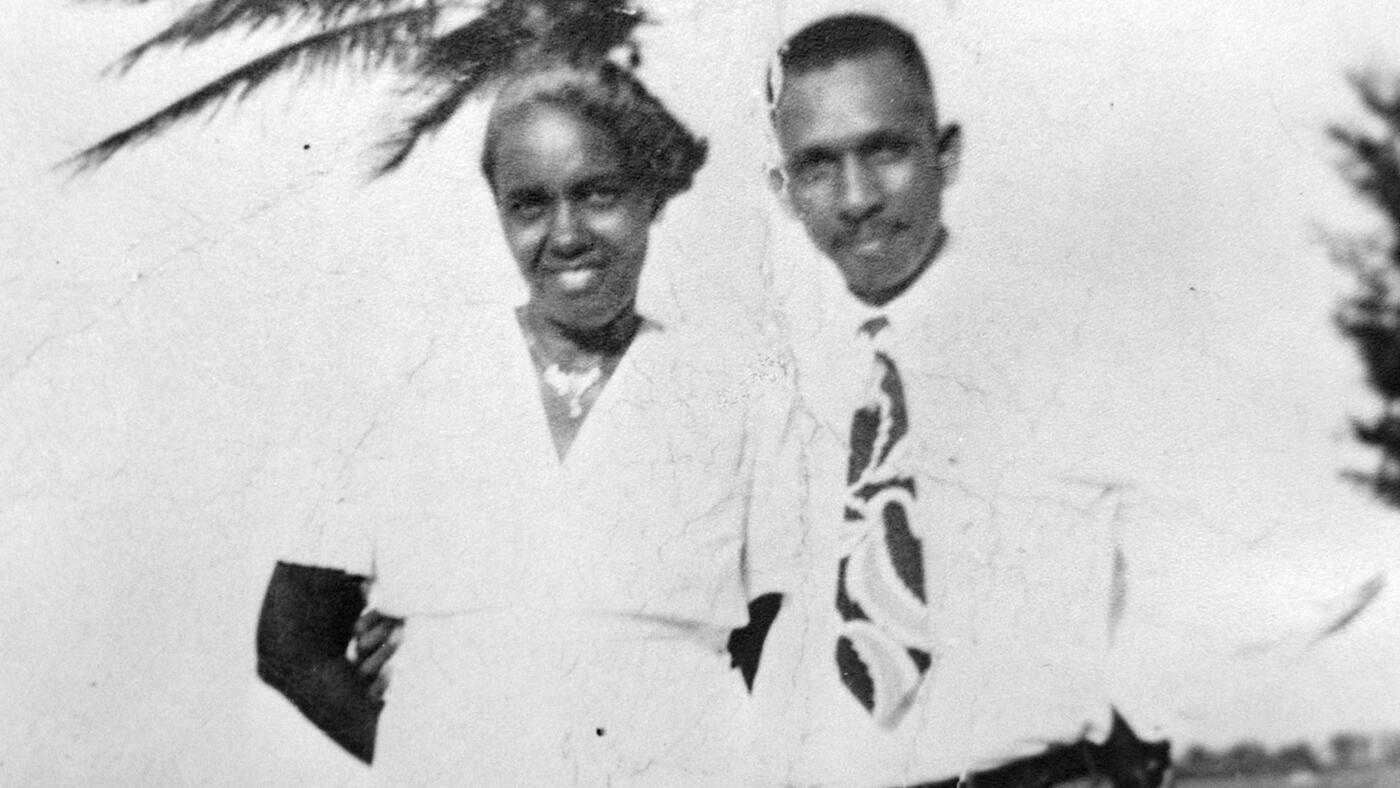

Harry and Harriette Moore

December 25, 1951 / Mims, Florida

Although less well known than some civil rights figures, Harry Moore pursued the cause of racial equality with a dedication that eventually cost him his job and his life. Moore and his wife Harriette,

both teachers in all-Black schools in Mims, Florida, were committed to the improvement of Black lives before becoming actively involved with the NAACP in 1934, when he founded the Brevard County chapter. As his activist passions grew, he filed a lawsuit for equal pay among white and Black teachers in 1937 and took on the issue of lynchings

in Florida in 1943. (At the time, the state had the highest per-capita lynching rate.)

But his activism came at a price. In 1946, Harry’s involvement with the NAACP caused the couple to lose their teaching positions. In turn, he became a full-time paid organizer. As his association and work with the civil rights group

intensified, so did the risk—especially after he became involved with the infamous 1949 Groveland rape case. After four young Black men were accused of raping a white woman, three were severely beaten while in police custody and the other

was shot more than 400 times after escaping.

Conviction by an all-white jury followed, and Harry campaigned to appeal their case and have Sheriff Willis McCall held responsible for their torture. A long legal battle resulted in the Supreme Court overturning the young men’s convictions

but ended with McCall shooting two of the defendants while escorting them to their new trial—killing one and critically injuring the other. Harry, infuriated, called for McCall’s suspension and indictment.

Six weeks later, on Christmas night 1951, the couple’s 25th wedding anniversary, a bomb exploded beneath their bed. Harry died before reaching the hospital, and Harriette died nine days later.

‘It seems that I hear Harry Moore.

From the earth his voice cries,

No bomb can kill the dreams I hold—

For freedom never dies!’

// A verse from ‘Ballad of Harry Moore,’ by Langston Hughes

The Moores’ murder, unsolved to this day, became known as one of the first lynchings of the civil

rights movement. News of the assassination spread swiftly, shocking and invigorating the country. Baseball legend Jackie

Robinson, soon-to-be Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall and even First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt all spoke out against the targeted attack. Famed writer Langston Hughes honored and grieved the activist’s life with his poem “Ballad of Harry T. Moore.” Hundreds attended the

activist’s funeral, and President Harry S. Truman was flooded with telegrams and letters protesting the assassination.

Although the Moores’ murder eventually faded into the sea of lynchings in American history, it garnered great attention at the time and raised wider awareness of the burgeoning civil rights struggle.

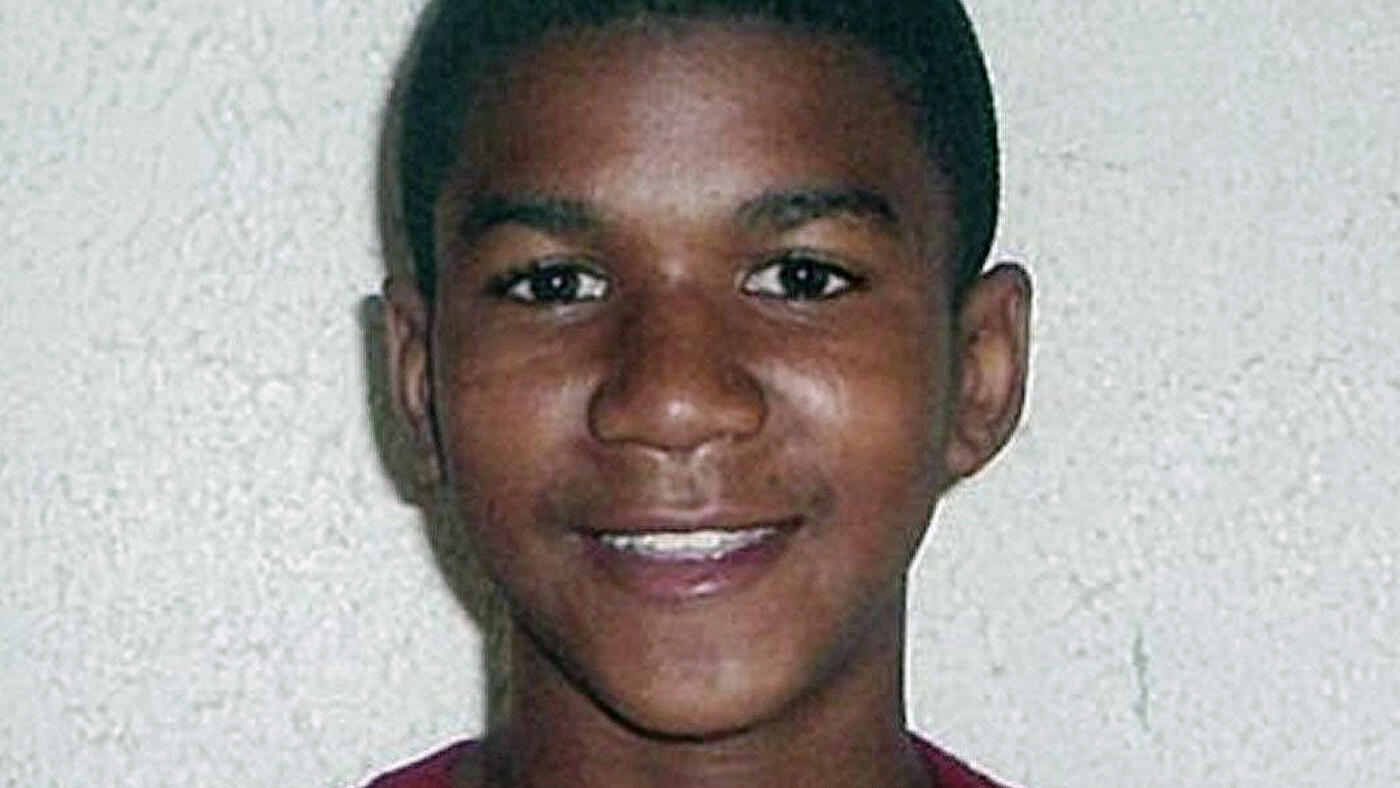

Trayvon Martin

February 26, 2012 / Sanford, Florida

Nearly 60 years after Emmett Till’s lynching, the killing of another Black teen—Trayvon Martin—shook the nation and incited a movement. But before the 17-year-old became an involuntary martyr, he was a

high school student who loved video games and math class, looked forward to his junior prom and

aspired to work with planes—even attending aviation school. But like so many Black people before him, his life was cut short, swiftly and unexpectedly, for no reason.

On the night he was killed, Martin was visiting his father in Sanford, Florida, during a 10-day high school suspension. Within the gated community, a series of recent break-ins prompted George Zimmerman—member of the neighborhood watch—to

follow the teen as he walked home from a convenience store, even though law enforcement told him not to pursue. Martin, on the phone with his girlfriend, expressed concern about being tailed and began to run. What followed was a clash

between the two, which left the unarmed teen dead from a gunshot to the chest, less than 100 yards from his front door.

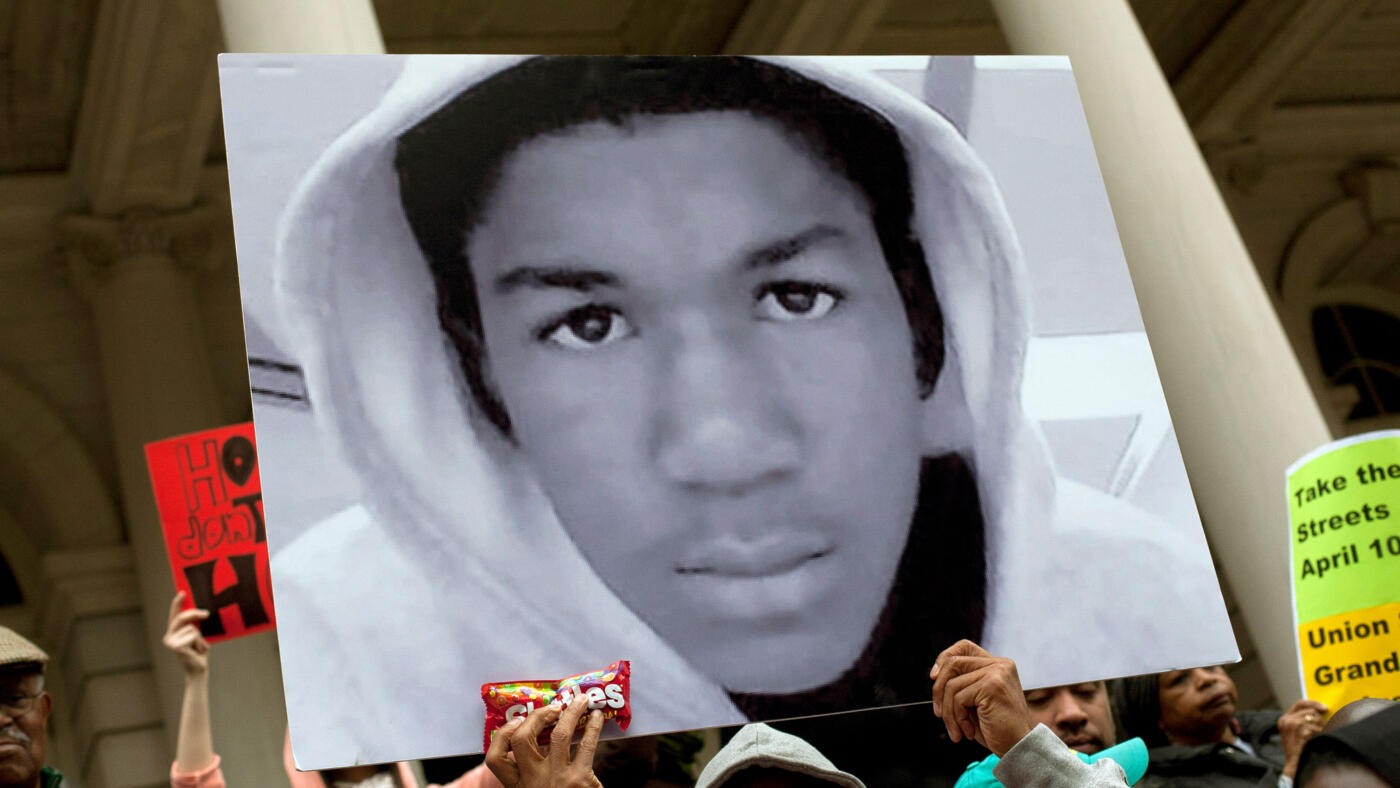

Of the many parallels drawn between Martin and Till’s deaths, one of the most potent was the involvement of their grief-stricken, determined parents. Unsatisfied with the police investigation into the death of their son after watching

Zimmerman walk free, claiming self-defense, Tracy Martin and Sybrina Fulton took their fight straight to the people. Their Change.org petition calling for Zimmerman’s prosecution garnered more than 2 million signatures, becoming the fastest growing campaign in the site’s history. Shortly after, the hashtag #Trayvon began trending on Twitter, and

then-President Barack Obama spoke out about the killing.

‘When Trayvon Martin was first shot, I said that this could have been my son... I think it’s important to recognize that the African American community is looking at this issue through a set of experiences and a history that doesn’t go

away.’

// 2013 comments by former President Barack Obama

Martin’s killing represented an outrage that Black Americans had seen and experienced firsthand much too often—typically with no justice. However, amidst growing public outcry, Zimmerman was charged with second-degree murder on April 11. His

July 2013 exoneration, based largely on Florida’s controversial “stand-your-ground” law, sparked protests nationwide, igniting a renewed fight for racial justice.

In the same month Zimmerman went free, the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter was

born. The phrase would become a rallying cry for justice when Black Americans are killed. And it would come to define a fiercely committed new generation of civil rights activism aimed at ending a legacy of hate, violence and callous

disregard for human life.