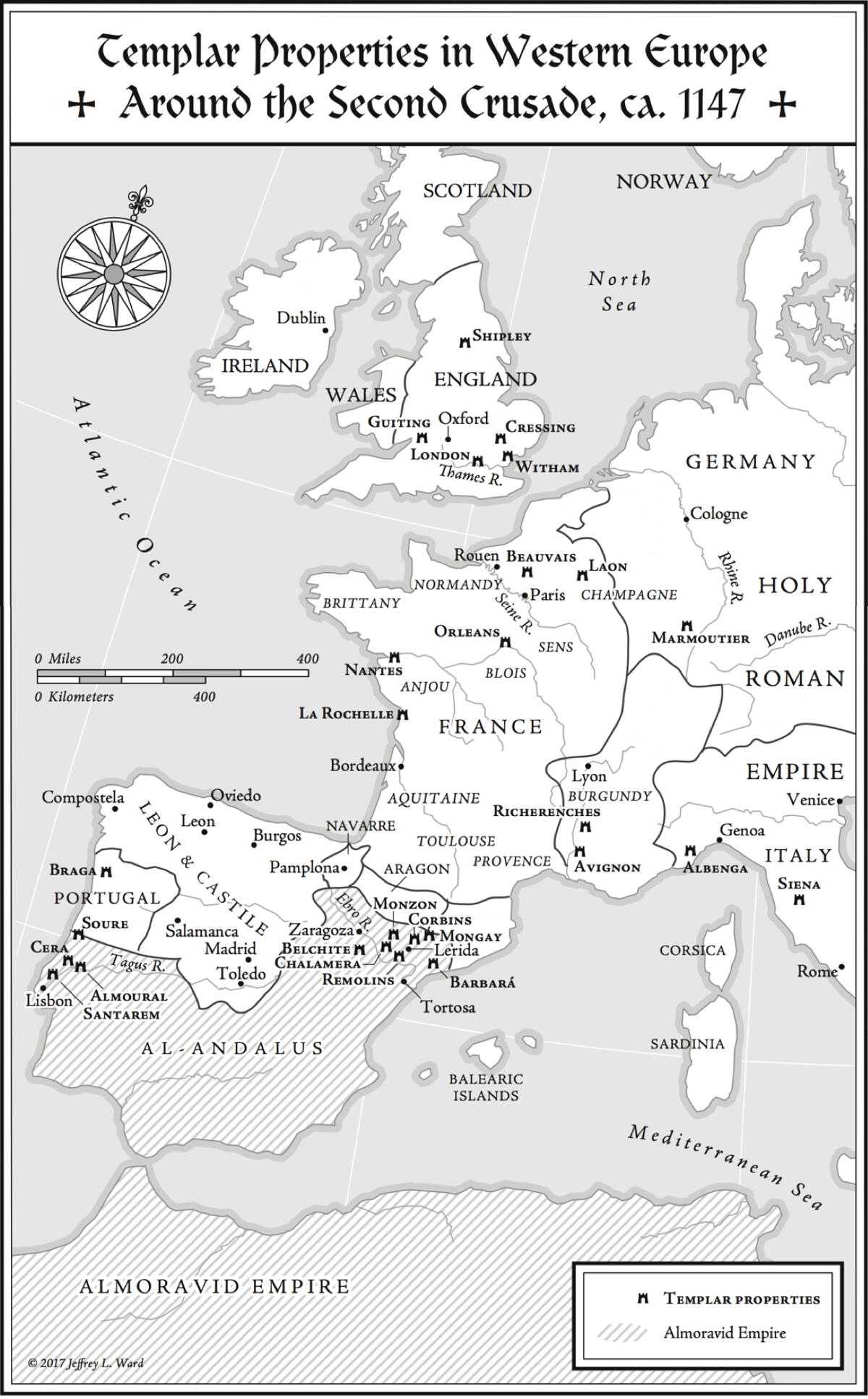

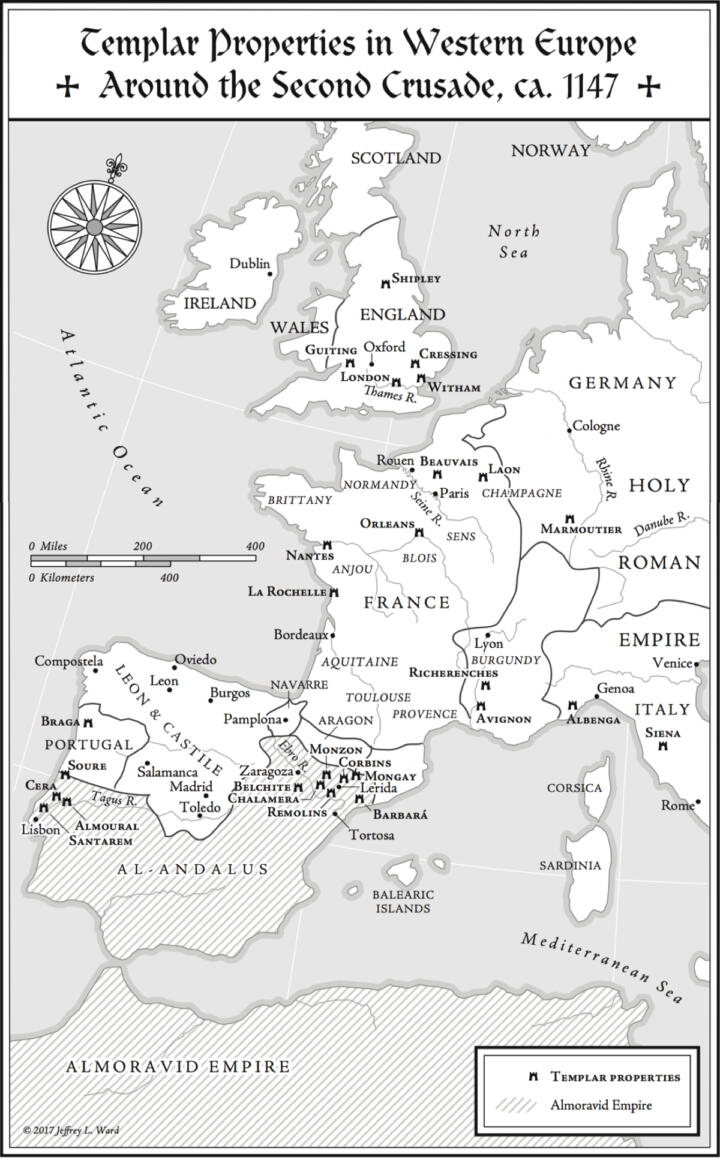

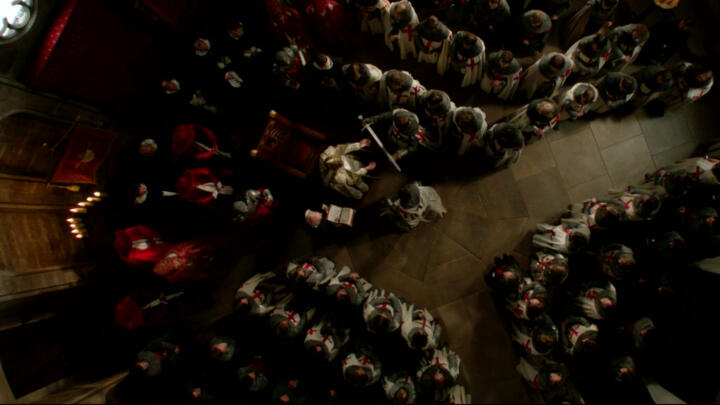

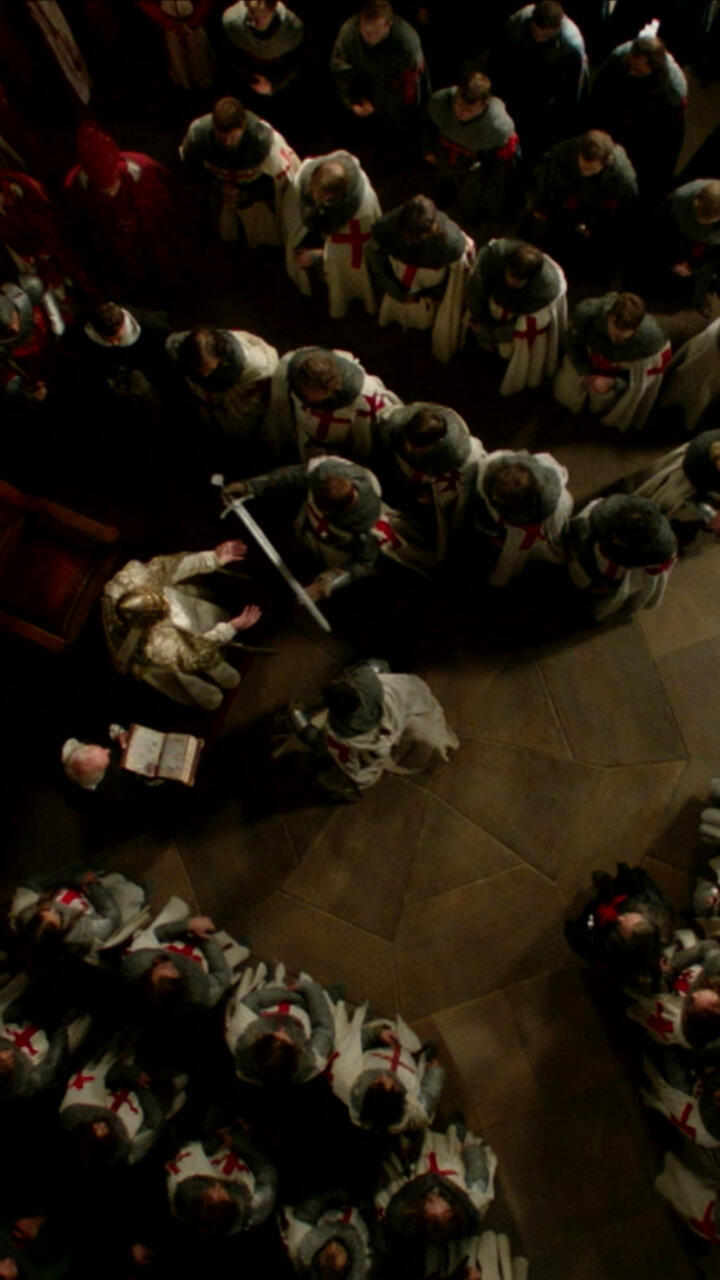

In 1220 it was exactly a century since Hugh of Payns had established the Order of the Poor Knights of the Temple of Solomon in Jerusalem. During those 100 years, the Templars had transformed from indigent shepherds of the pilgrim roads, dependent on the charity of fellow pilgrims for their food and clothes, into a borderless, self-sustaining paramilitary group funded by large-scale estate management.

By the early 13th century they were political players with contacts at royal courts across Europe and property magnates whose estates stretched from Scotland to Sicily. They had also become crack soldiers who could afford to build gigantic amphibious bases in war zones and financial experts co-opted into the bureaucratic machinery of Christendom’s leading kingdoms.

The Templars were respected and valued throughout the Christian world, but they plainly could no longer be thought of as radical, uncompromising ascetics. Their grand master, who in 1220 was Peter of Montaigu, was entitled, under the Rule of the Templars, to an impressive entourage, including four warhorses, up to four pack animals and a personal retinue including a chaplain, clerk, valet, sergeant, farrier, Saracen translator, a cook, a three-man bodyguard team and a Syrian mercenary known as a turcopole. In addition, he had a strongbox for keeping all his valuables and could access a private room for his own use within whichever Templar palace he was visiting.