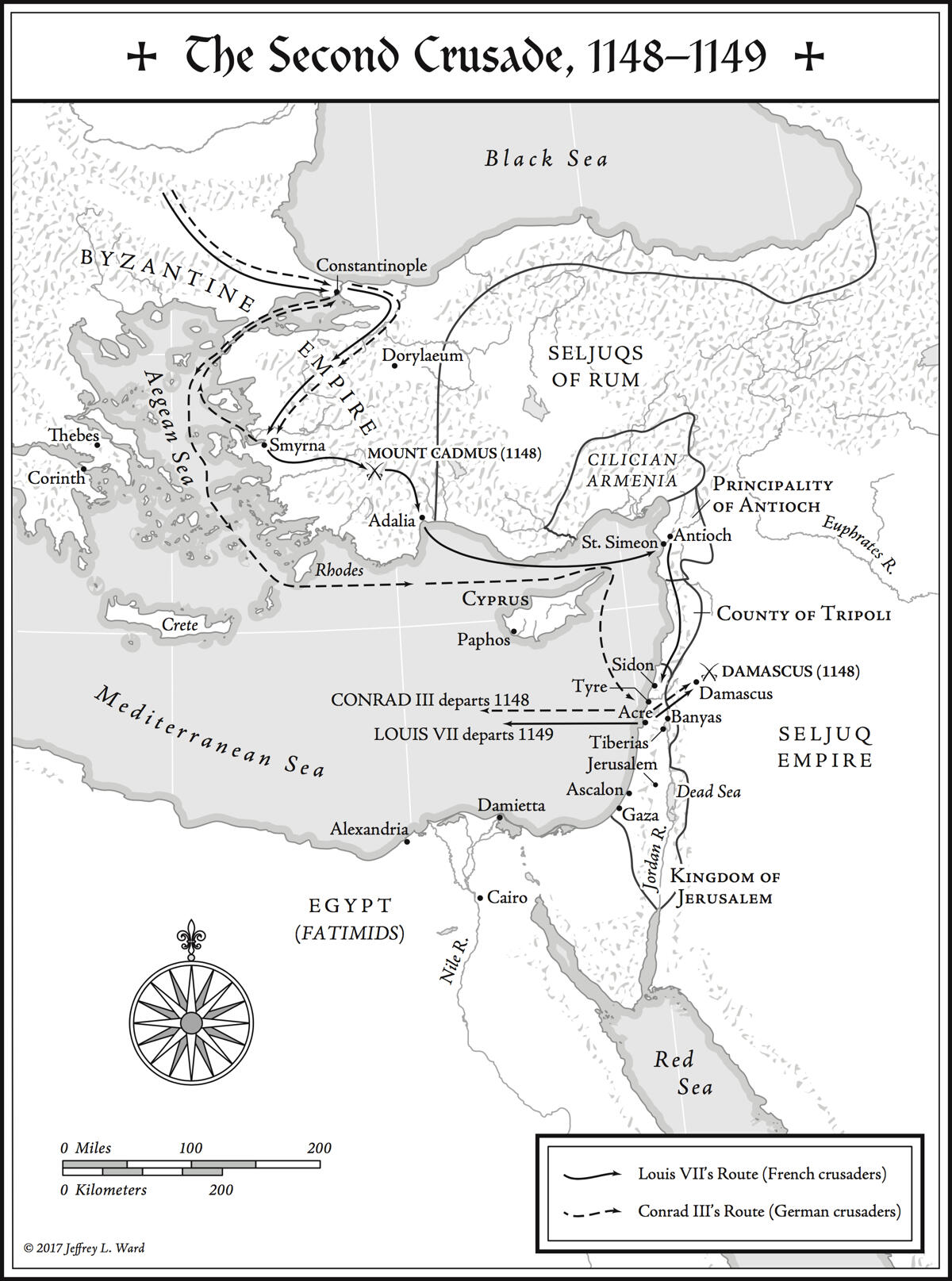

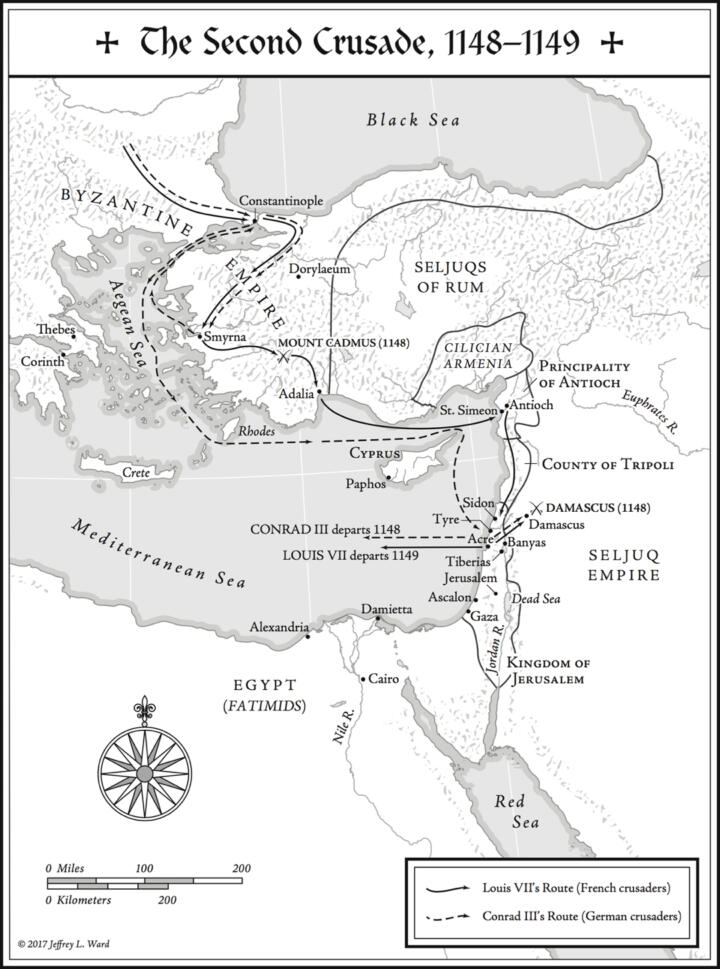

At Easter in 1147, 130 Templar knights assembled in Paris, drawn there as part of a huge army gathered to join the Second Crusade to liberate the city of Edessa in the Holy Land. The knights would have been a striking sight, wearing white mantles with a red cross emblazoned across their uniforms.

Leading the French crusaders was King Louis VII, whose personal piety was such a hallmark of his kingship that his wife, the fiercely intelligent southern duchess Eleanor of Aquitaine, sometimes wondered if she had married a monk and not a king. Tears were shed and prayers recited by the crowd who had come to see the king leave. Not for 50 years had there been such crusading fervor in the West.

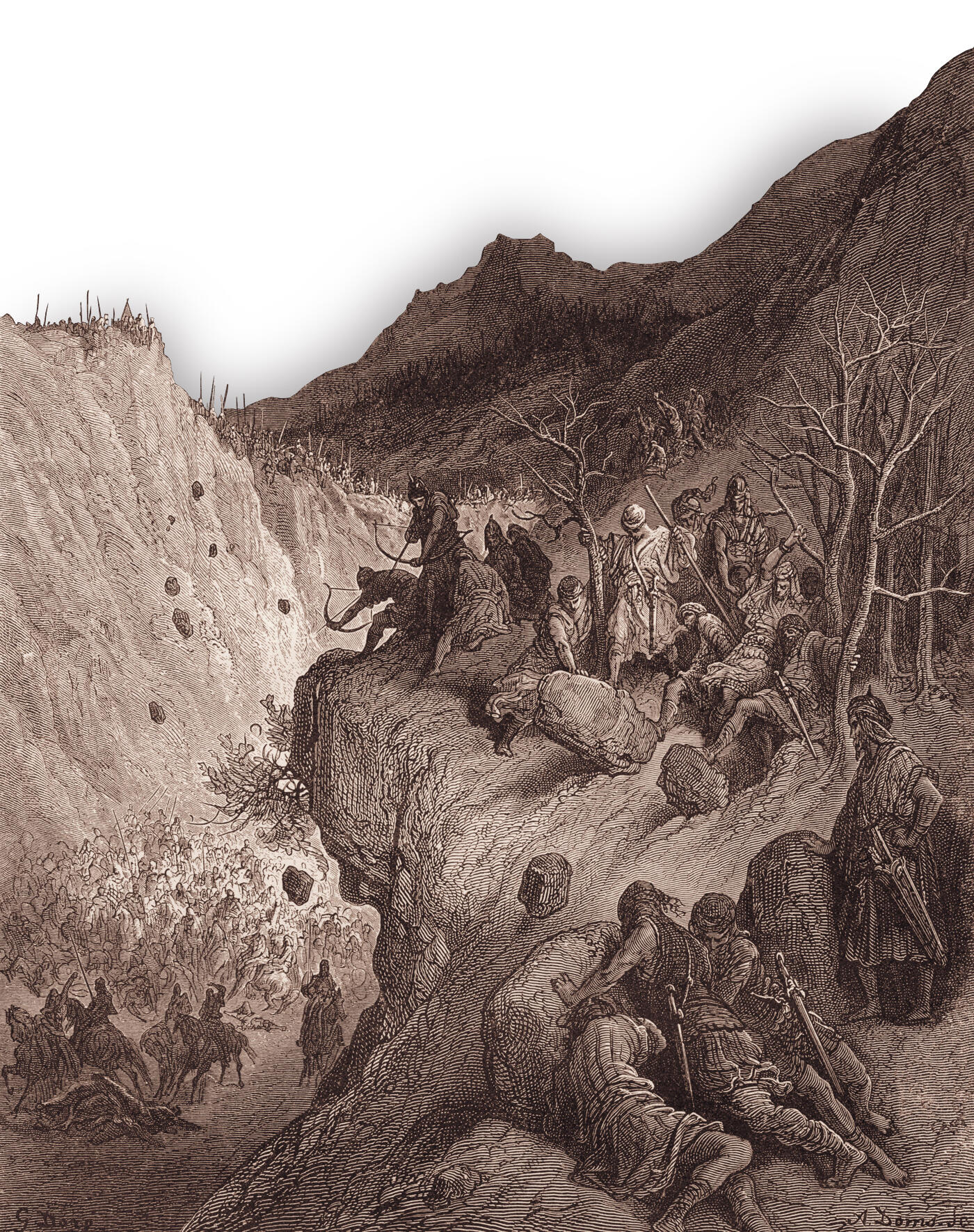

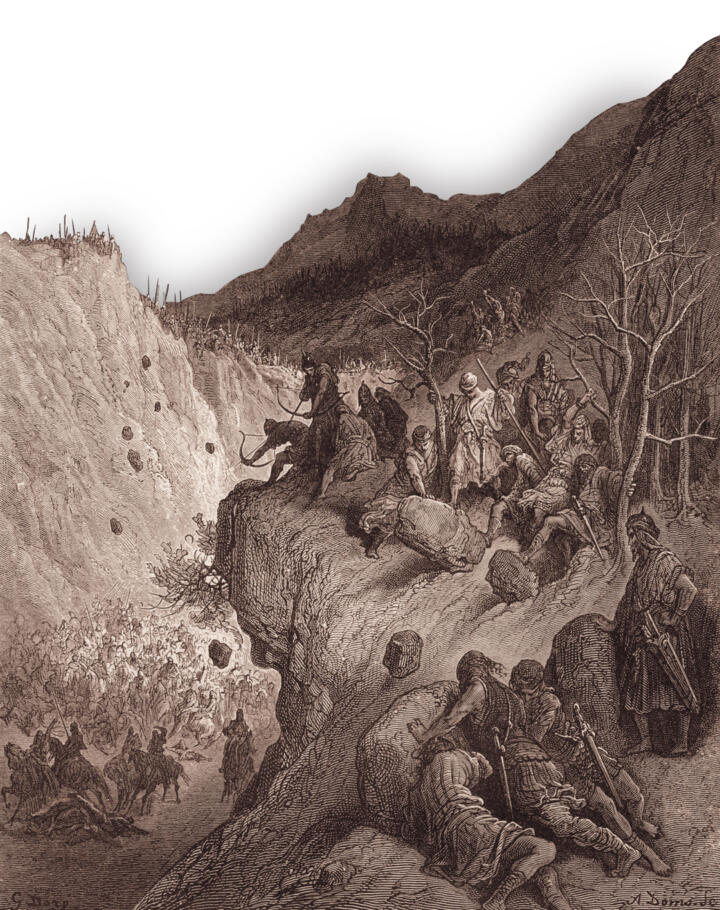

Little by little, as Louis’s forces made their way east, it became clear that his army was in fact little more than a pious but incompetent rabble. Were it not for the Knights of the Temple, it is likely they would never have made it within sight of the Holy Land at all.