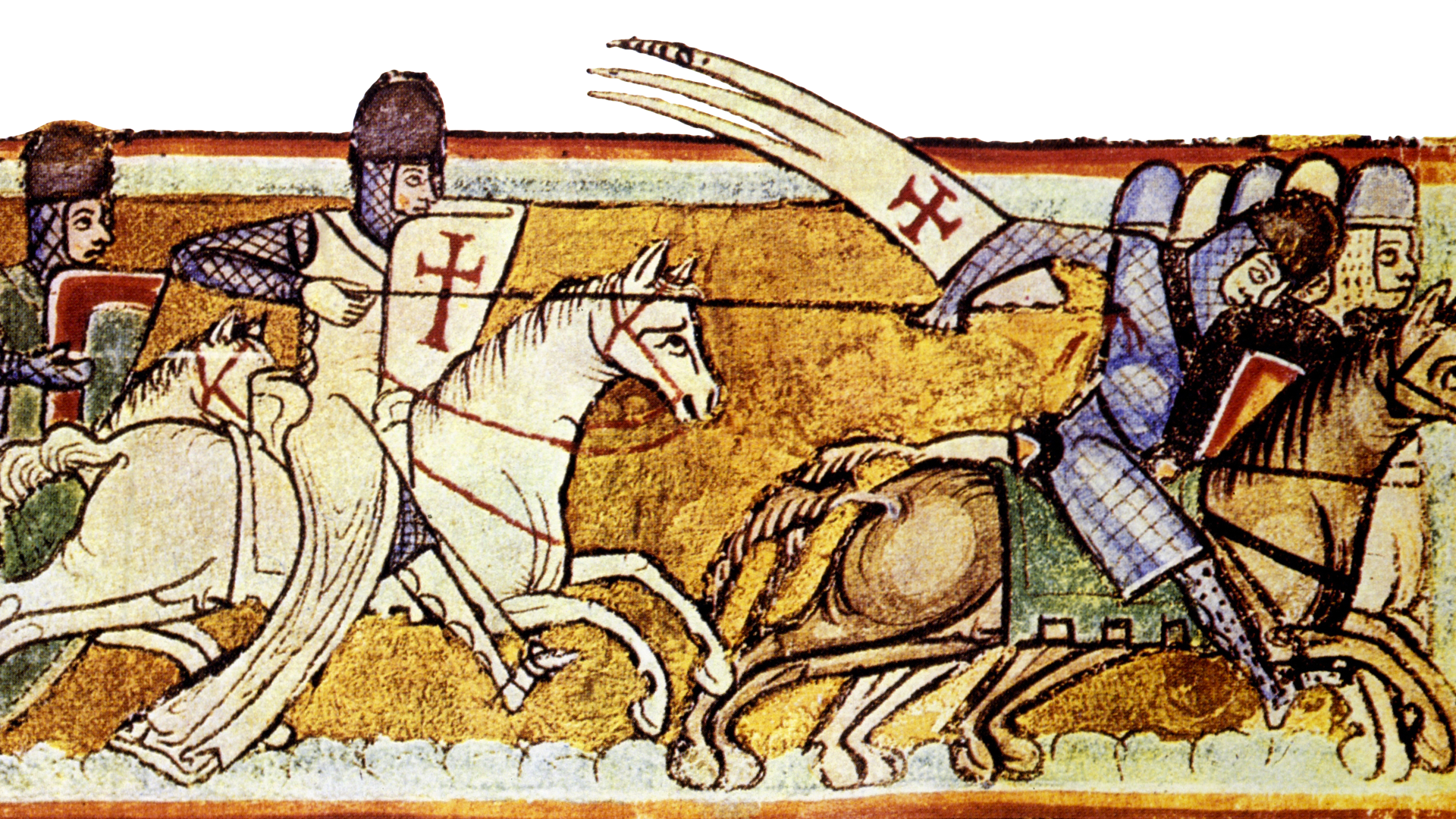

Between 1200 and 1210 the German writer Wolfram von Eschenbach composed an epic romantic poem, tens of thousands of lines long, called Parzival. It drew on the hugely popular legends of King Arthur, which had for decades delighted aristocratic audiences with tales of chivalry and questing, love and betrayal, magic and combat.

Eschenbach’s patron was one Hermann, Landgrave of Thurangia, but the readership his work eventually found was enormous and its influence immense. More than 80 medieval manuscripts of the poem still survive.

In Parzival, the eponymous young hero appears at Arthur’s court and quickly becomes embroiled in a dispute with a “red knight,” whom he kills in a fight. After going away to learn to be more chivalrous, Parzival embarks on a search for something called the Grail: both a literal hunt for a mysterious, life-giving stone and a spiritual journey toward enlightenment in God. The Grail is initially guarded in a magical castle by a character called the Fisher King, who is in constant pain from a wound to his leg, divine punishment for his failure to remain chaste.